In a world ruled by screens and software, the most radical tool on an architect’s desk might still be a wooden pencil.

The Return of the Line

For decades, AutoCAD, Revit, Rhino, and BIM and other platforms have dominated Architectural design, sketching came to be seen as quaint, even obsolete. But walk into the studios of many architects today and you will find sketchbooks lying open beside the computer screens.

A quiet revolution is underway around the world. From Tokyo to Copenhagen to Mumbai, Architects are drawing again. Not for sentimentality, but because they are rediscovering that the pencil is still their best tool for thinking.

Digital Fatigue

For years, the profession has raced toward precision. Every wall thickness, every daylight study, every material texture could be modeled with incredible accuracy. The digital age promised total control and the ability to optimize every inch of a building before a single brick was laid.

But, we lost something in that race.

Many architects now speak of digital fatigue, the exhaustion of endless clicking and zooming. Screens demand perfection before ideas even had a chance to breathe. Software lets designers zoom in, but it makes it harder to step back.

The loss is not only visual. It is tactile and cognitive. Architects who learned on paper know that drawing is not just representation, it is reasoning. The hand does not merely follow thought, it also provokes it.

As a NYC and Paris-based architect, I often tell young designers:

“Your digital tools make you precise, but your sketches make you present.”

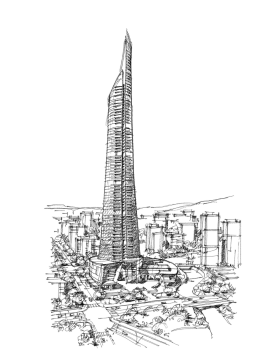

There is a moment in every project when the architect’s mind and hand meet and vague ideas are captured into lines. That is where the sketch lives.

Michael Graves once said, “The hand will find things that the mind doesn’t.”

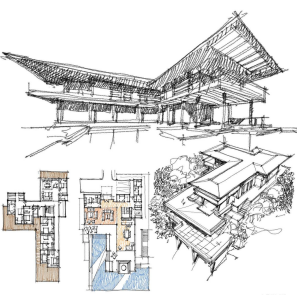

Sketching allows for hesitation, mistakes, and intuition. These are the very elements software tends to filter out. A crooked line can trigger a new idea. A smudge can become a courtyard. A shadow, an entire façade.

Sketching is not a step before design, it IS design.

Few contemporary architects embody this more than Steven Holl, whose sketches serve as the conceptual backbone of his work.

The New Hybrid Era

The digital age has not killed sketching yet, it seems to be reviving it.

Many designers are now using a hybrid workflows. They sketch directly on tablets or iPads. Apps like Morpholio, Concepts, and Procreate have turned digital devices into digital sketchbooks. They merge the fluidity of hand drawing with the power of digital editing.

Norman Foster once said, “Sketching is the beginning of the dialogue between the architect and the idea.”

Today, that dialogue simply spans more mediums.

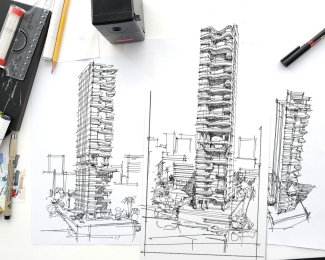

I have seen this first-hand. In every major client presentation I give, I deliberately include my hand sketches. From Mumbai and across India, the reaction is always the same: clients lean in, engage with the concept. They see sketches as proof of personal engagement, not just a programmatic solution produced by software.

Hand drawings are reappearing in presentations and social portfolios because they humanize architecture. They convey warmth, intention, and atmosphere. These are qualities most photo-realistic renders struggle to evoke.

Meanwhile, AI-generated imagery is rapidly eroding the “wow factor” that used to belong to digital renderings. What used to take hours or days now takes seconds. And paradoxically, this tidal wave of “perfection” has made the imperfect pencil line more valuable than ever, because it comes across as original.

In an era when AI can conjure up entire buildings in moments, architects are rediscovering the emotional weight and the value of the hand drawing. A sketch is like a lovingly prepared home-cooked meal, deeply human, something no fast-food render can replicate.

Learning to See Again

The revival of drawing is not only happening in practice, it is also happening in schools.

When I visited Amity University in Mumbai last year, I was delighted to find hand-drawn presentations pinned up across the studios. It reminded me of my Architectural school days in Paris.

Many professors are once again insisting that the first step of every project be analog. Sketching slows the designer down. It makes decision-making material. It reconnects thinking with the human scale.

This shift reflects a deeper recognition: design is not only about generating geometry, it is about cultivating perception. Students who draw learn to look at the world more directly rather than seen it though a screen.

The value of the designer is not in prompting an AI agent, it is in engaging the project personally.

A Profession Redefining Itself

Architecture has always evolved with technology. The pencil replaced the stylus and the computer replaced the drafting board. The current return to hand drawing is not a rejection of progress, it is a refinement of it.

It reflects a profession seeking balance between intuition and intelligence, craft and computation.

The best architects today are bilingual: fluent in both hand and code.

In studios around the world, concept sketches are scanned and layered into digital models; paper studies inform parametric scripts; freehand diagrams drive sustainability strategies. The future is not analog against digital, it is a conversation between them.

Drawing the Future

As the design world accelerates toward automation, the simple act of drawing feels almost radical. It reminds us that architecture is ultimately about perception and how humans experience volumes, space, and light.

A sketch cannot compete with the precision of a BIM model or the speed of an AI generator. But it does not have to. It offers something much rarer, a direct, un-mediated link between imagination and reality.

When an architect picks up a pencil today, they are not turning back time. They are reconnecting with the essence of their craft, the place where ideas are born.

Because before a building is completed, it begins as a line. It is fragile, human, and full of possibility.