Basque Country International Architecture Biennial – Mugak/2025

Throughout history, the concept of utopia has been a powerful tool for imagining possible worlds — for projecting fairer, more equitable, or transformative visions of the future. However, this imaginary has been profoundly shaped by a masculine and Western perspective that has monopolised utopian narratives in disciplines such as philosophy, politics and literature. Notable figures such as Saint Augustine, Thomas More, Charles Fourier, Karl Marx, and George Orwell have shaped this tradition. However, there appears to be a paucity of utopias conceived by women. What forms might they take if imagined from other bodies, other forms of knowledge and other lived experiences?

One of the earliest answers to these questions can be found in the work of Christine de Pizan, a pioneer in envisioning utopia from a female perspective. In The City of Ladies (1405), Pizan builds a symbolic city where women are not only worthy of respect but also protagonists and custodians of thought, education, and politics. Despite its moral and philosophical significance, this work has been historically marginalised, as have the writings of authors such as Lady Mary Chudleigh or Lucrezia Marinella. The suppression of these voices highlights the necessity to re-evaluate the history of ideas, incorporating diverse perspectives to envision a more inclusive future.

This project, entitled Lightness and Protest: Embroidery as a Feminine Utopia — emerges from the desire to reverse that exclusion: not only to give voice to those who have been historically silenced, but also to propose new ways of imagining utopia itself. We advocate for a democratic, sensitive, and plural utopia, one that recognises care, diversity, and collective participation as fundamental pillars in building the imaginaries of the future.

To achieve this, we propose a change in both the content and the languages of utopia. In contrast to philosophical treatises written for an elite, our project draws on embroidery, sewing, and basketry — crafts historically associated with the domestic, the feminine, the detailed, and the “minor” from the perspective of academic art — which today are re-signified as powerful tools of activism and participation.

The term ‘craftivism’, coined by Betsy Greer in 2003, refers precisely to this political use of hand-making. The embroidered banners of British suffragists between 1901 and 1908, or the arpilleras made by Chilean women such as Violeta Parra during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship, demonstrate the potential of thread to serve as a medium for memory, protest and active community-building. Embroidery is more than mere decoration; it is a means of marking, narrating, transforming and denouncing. The seemingly innocuous and even irrelevant appearance of embroidery has functioned as a genuine Trojan horse, carrying subversive political messages and proposals for genuine lifestyle change within it.

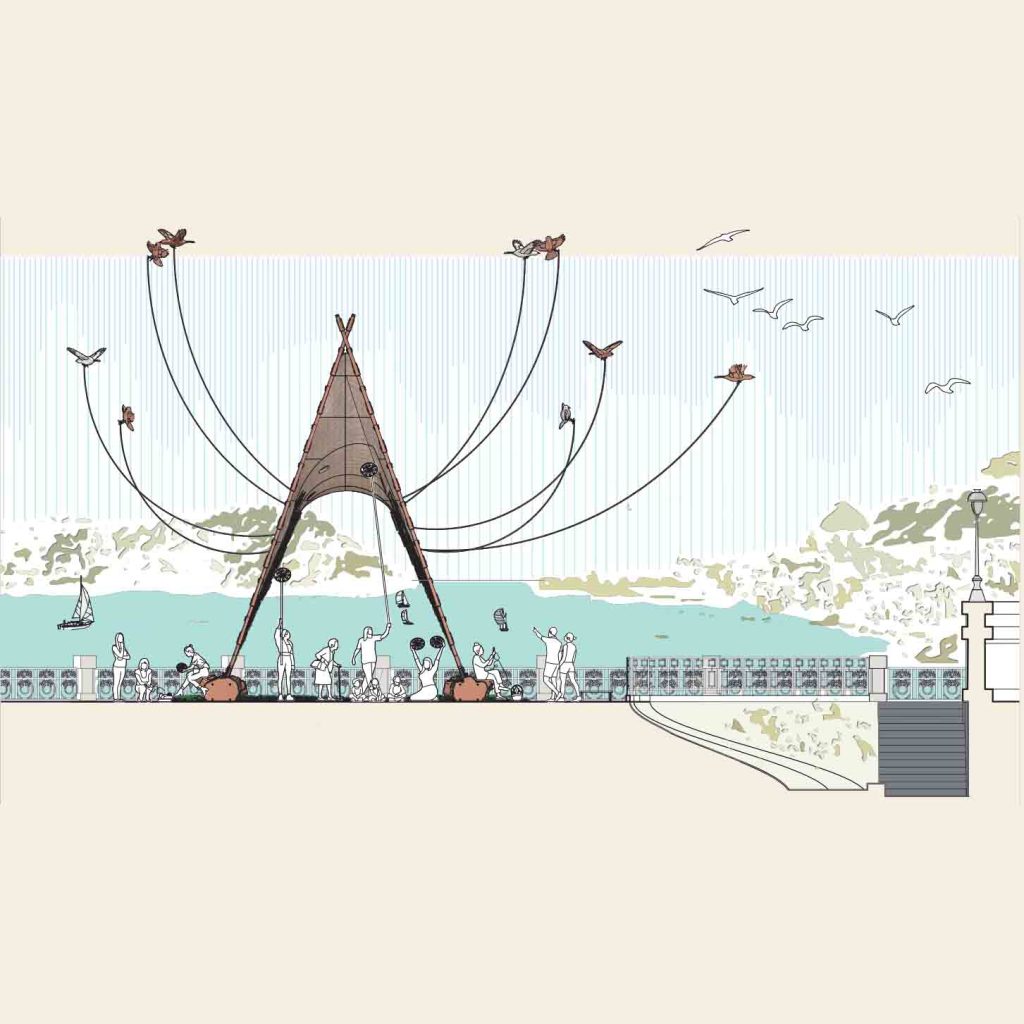

In our pavilion, we use 3D printing technology to create a series of hoops that reproduce traditional Basque embroidery patterns, while also incorporating motifs of political awareness. These embroideries raise awareness of pressing issues such as rising housing prices, the threat to urban pollinators, the deterioration of marine ecosystems, individual responsibility in caregiving, the effects of mass tourism in San Sebastián, and gender inequality in access to the architectural profession.

Today, works such as A Little Book of Craftivism (2013) and How To Be A Craftivist (2017) by Sarah Corbett offer a different kind of revolution: citizens who cease to be merely, or primarily, consumers. Our pavilion, constructed for the Mugak/2025 Biennale, is designed to serve as a forum for the exploration of utopias. Rather than simply representing an idea, it invites citizens – especially women, older people, children, and caregivers – to express themselves collectively through the act of stitching. Each thread, message and symbol represents a collaborative effort to imagine the future.

Basque Symbols: Freedom, Identity, and Utopia

The pavilion is not merely a functional structure; it is also culturally situated, designed specifically for its site, and paying tribute to key symbols of Basque culture — all of which are linked to fundamental values for thinking about utopia: freedom, identity, and belonging. Among them:

The Tree of Gernika

It is a symbol of the traditional liberties of Bizkaia. In homage to this history of self-governance and resilience, the bases of our pavilion are shaped like tree trunks. The structural supports thus physically embody this commitment to freedom, anchoring utopia in the collective memory of the territory.

The Kaikus

The term ‘kaiku’ is also traditionally used to refer to a knitted jacket, known as a ‘kaiku’, that is typical of Basque festivities. These are often woven by grandmothers (‘amona’) for their grandchildren. These garments frequently incorporated embroidery of the six coats of arms of Euskal Herria. Our project draws inspiration from these motifs, transforming them into abstract patterns that form the base of the embroidered modules — blending the traditional with the contemporary.

The Railing of La Concha Promenade:

This railing was designed in 1910 and has since become an emblem of Donostia. The compositional language of our pavilion serves as the foundation for the embroidery modules, inviting each participant to create their own version inspired by their personal interpretations of the city. This approach fosters a dialogue between the collective and the individual, as well as between urban symbolism and civic imagination.

A Place for Collective Imagination

The pavilion has a clear social purpose as well as being symbolic. Its design allows for multiple uses that encourage participation and public expression.

Embroidering Utopias: The pavilion’s primary function is to serve as a space for collective embroidery. It features hoops adapted for people of all ages and abilities, which can be used on benches resembling fallen tree trunks or directly on the ground, resembling a bed of dry leaves. These hoops have a fastening system that enables them to be attached to the pavilion’s structure, thereby integrating the embroidery into the architecture itself.

Collective childcare: The pavilion can be closed at its ends to create a safe area for childcare. Workshops can take place inside while, outside, mothers, fathers and other carers can gather to discuss and propose policies that incorporate the perspective of care.

Visibility and inclusion: Strategically located opposite a playground and La Concha beach, the pavilion enables caregivers to participate in public forums while keeping an eye on their charges. This ensures that the voices of those who are often excluded from political conversations are heard.

Cinema, assemblies, and climate protection: The hyperbolic paraboloid-inspired roof provides shade and shelter from the rain, allowing for outdoor activities such as assemblies, film screenings, and talks. The pavilion’s light and resilient geometry serves as a metaphor for utopia: flexible, open and enduring.

A technical structure that is characterised by its adherence to its own principles.

The pavilion incorporates advanced 3D printing technology, allowing for structural optimisation that minimises material use without compromising stability. The perforated roof modules are engineered to resist wind loads and evoke the embroidery of véhiculaire; their motifs include leaves, birds, and provincial shields, linking nature, identity, and collective desire. The embroidery patterns intentionally disrupt their regularity, serving as a reminder of pressing global issues such as over-tourism, housing crises, biodiversity loss, and marine degradation.

All materials used in our products, including those for 3D printing, are selected with the principles of the circular economy in mind. We use pellets and filament made from recycled packaging and ocean-cleaning plastics. The textile elements are made from recycled sailcloth. The pavilion’s structure and materiality thus embody a utopian concept: a circular production process in which industry is not a threat to the environment, but a guarantor of its preservation and regeneration.

A Utopia Woven by Many Hands

In a world saturated with top-down discourses and technocratic solutions, this project chooses to support bottom-up cultural production — to vindicate the manual, the collective, the sensitive. In contrast to the traditional image of the ivory tower, we present a shared embroidery hoop as a symbol of collaboration and community. The manifesto is not supported by this action. We are committed to facilitating open dialogue in the absence of dogma.

Lightness and Protest is a feminine, plural utopia. It is a space that acknowledges the political value of care, of participation and civic engagement, of craftsmanship and collaboration. It does not promise paradise, but it invites us to build it, stitch by stitch, from the common ground. In this collaborative endeavour, comprising elements such as leaves, threads, memories and desires, we have the opportunity to explore novel approaches to conceptualising the city and to reimagine our collective existence in the world.

Mandatory credits for any publication:

Architecture: Izaskun Chinchilla Architects

Commissioned by: Basque Country International Architecture Biennial – Mugak/2025

Photography: Erlantz Biderbost